The Gay Man with the Golden Gun?

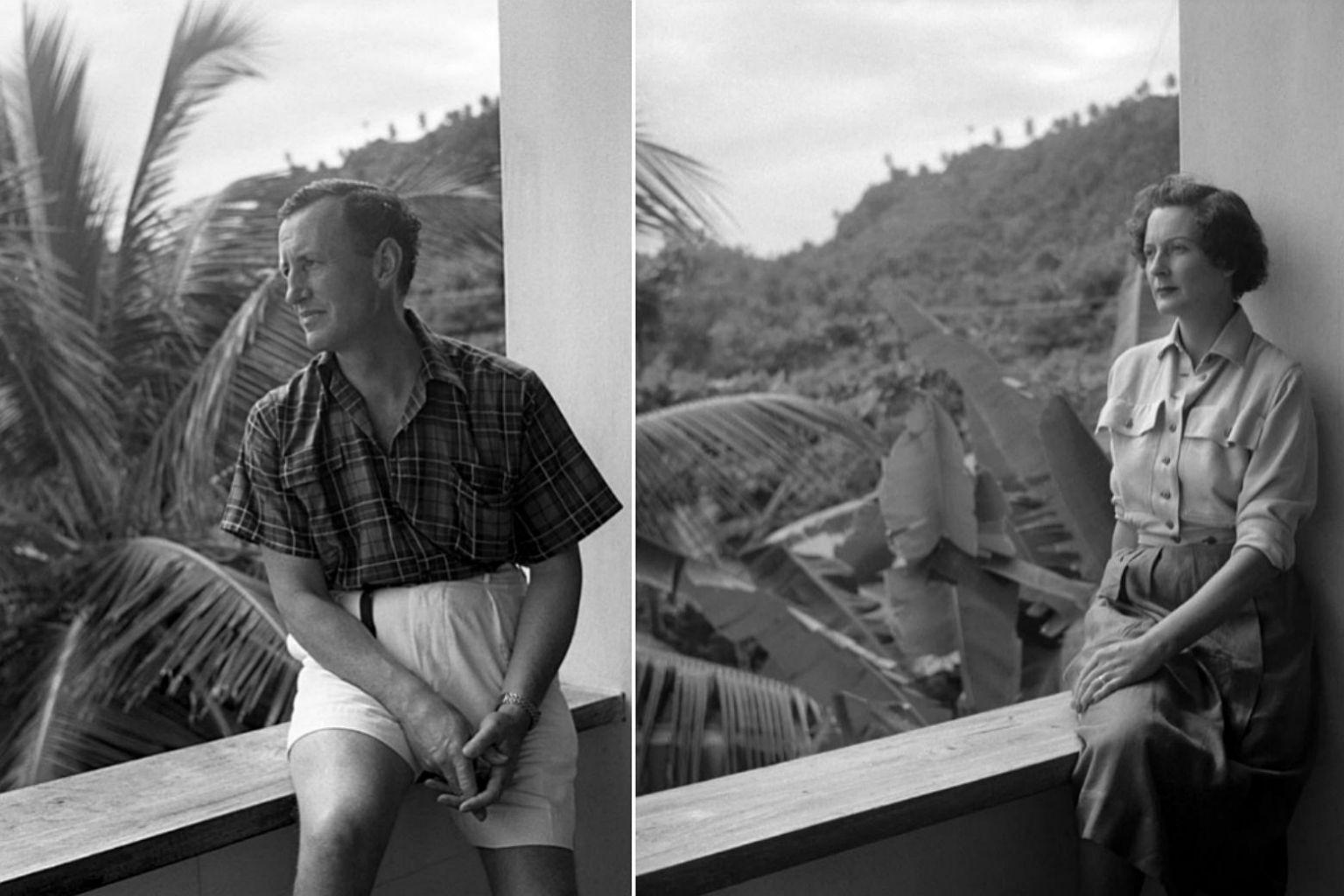

The Man with the Golden Gun was Ian Fleming's final novel before his death in 1964. In his previous novel, You Only Live Twice, Bond had lost his memory after his final confrontation with Blofeld and thought he really was the Japanese fisherman he had assumed the cover of. He also thought the name of the Russian city of Vladivostok had some connection to him so had set off there to try and discover his past.

Golden Gun starts with Bond returning to London and calling the Secret Service to try to establish his identity. He has been brainwashed by the Russians and had been sent to kill M, whose name we finally discover is Admiral Sir Miles Messervy.

Bond's assassination attempt on M fails, and Bond is sent to recuperate. M decides not to fire him — he wants to de-brainwash him and send him back out to fight the Russians. Eventually, he gives him the target of KGB assassin, Francisco Scaramanga. Bond is sent to the Caribbean to track him down.

Interestingly, Fleming hints that Scaramanga may be homosexual. Kingsley Amis (who worked on some corrections of the proof after Fleming's death) thinks that Fleming had originally intended Scaramanga to be sexually attracted to Bond (see the excerpt of a letter from Amis written on 5 October 1964 at the end of this article).

He wonders whether there had been "a buggery thread" in Fleming's earlier manuscripts. This would certainly have been a very daring departure for the Bond series in the mid-1960s. Even today, there would be a lot of Bond fans who would explode in rage at the thought of Bond being involved in a gay experience to help with the mission — even in the film Skyfall, Bond did hint that it wasn't his "first time".

So could the future film series (or continuation novel series) ever include a mission where Bond has to seduce a man to get information? Could the Bond Boy ever become a thing?

Here is a lengthy excerpt from a letter Kingsley Amis wrote to Tom Maschler on 5 October 1964:

Have been driving hard at The Man with the Golden Gun. I forget what if anything, we arranged about this. Anyway, you may care to glance at the enclosed list of errors, etc. My own feeling in general is that, while some kinds of error could easily be spotted by a competent reader (repetition of words, the omission of question-marks — though I may say that none of Fleming's previous books has been thoroughly corrected for this — the 'Adams' mantelpiece, etc.), there are on the other hand several passages that need to be rewritten by someone with a feeling and flair for style: this is especially true of the 2½ pages of dialogue that will have to be entirely re-drafted (pp.127–129). Anyway, forgive me if some of the errors listed seem insultingly obvious.

My greatest discovery has been to spot what it is that has done most to make the book so feeble. As it stands, its most glaring weaknesses are:

i. Scaramanga's thinness and insipidity as a character, after a very lengthy though pretty competent and promising build-up on pp. 26–35;

ii. The radical and crippling implausibility whereby Scaramanga hires Bond as a security man (p.67) when he doesn't know him and, it transpires, doesn't need him. This is made much worse by Bond's suspicions, 'there was the strong smell of a trap about' and so on.

Now I am as sure as one could be in the circumstances that as first planned, perhaps as first drafted, the reason why Scaramanga asks Bond along to the Thunderbird is that he's sexually attracted to him, which disposes of difficulty no. ii right away and gives a strong pointer to the disposal of no. i. I wouldn't care to theorise about how far Scaramanga was made to go in the original draft; far enough no doubt, to take care of no. i.

At some later stage, Flemings own prudence or that of a friend induced him to take out this element, or most of it: see p.33–34, which as things are have no point whatever. He was unable to think of any alternative reason for Scaramanga's hiring of Bond, and no wonder, since the whole point of this hiring in the first version was that it had to be inexplicable by ordinary secret-agent standards. And then he was forced to hold on to the stuff about Bond's suspicions, and it's always better to leave an implausible loose end than make your hero look a nit.

There are no doubt all sorts of reasons why we can't have the book in its original version, the most telling of which is that it probably doesn't exist any more, if it ever did. I could re-jig it for you, but there are all sorts of reasons against that too. But if you think you could initiate a discreet inquiry about whether there was a buggery thread at some stage, I should be most interested to learn of any confirmation for my brilliant flash of insight.

I'm sending the typescript back under separate cover. We go to Molins the day after tomorrow. Ageda inquired kindly after you. Jane and I thoroughly enjoyed your stay with us and we're sorry to see you go. We send our love.

*!Hasta la vista!

Kingsley

Philip Whitfield

Philip has been a Bond fan since he was four years old. Dalton aficionado. Corbynista. Thinks Brosnan was shit.